The City of Decatur is considering a $242 million investment into its water and wastewater infrastructure through a series of debt issuances over the next four years. On Tuesday, city officials and Decatur water board members toured Decatur’s water and wastewater treatment plants, along with Kimley Horn engineers who discussed the current infrastructure and potential improvements.

Roddy Boston of Decatur Public Works shows the difference between the water that comes in and the water that comes out of Decatur’s water treatment plant.

The Messenger tagged along for the tour led by city staff and its engineers. The tour showcased the facilities and staff dedicated to treating water and wastewater, as well as how the city plans to adapt to current challenges and future growth.

Here’s how you get your water, what happens after it goes down the drain and information about potential upgrades that the city could pursue.

Photos by Austin Jackson of the Wise County Messenger

Raw water pump station at Lake Bridgeport

This line near the raw water pump station flows in to Lake Bridgeport.

Like most Wise County cities, Decatur’s water is pulled from Lake Bridgeport. A suction intake valve brings that lake water into a pipeline. It makes its first stop at Decatur’s raw water pump station near the lake’s dam. West Wise Special Utility District also operates a separate facility on the Tarrant Regional Water District land.

City of Decatur and Decatur Water Board officials tour the Wise County Water Supply raw water pump station.

Pre-treatment begins here with the injection of potassium permanganate, a strong chemical used in water treatment for oxidation and disinfection. It removes iron, manganese and hydrogen sulfide, which can cause discoloration, odor and taste issues.

The pre-treatment process has stained the exterior brick at the facility, which was never designed to handle this process. The new raw water pump station will be tailored to handle up to date treatments, according to city officials.

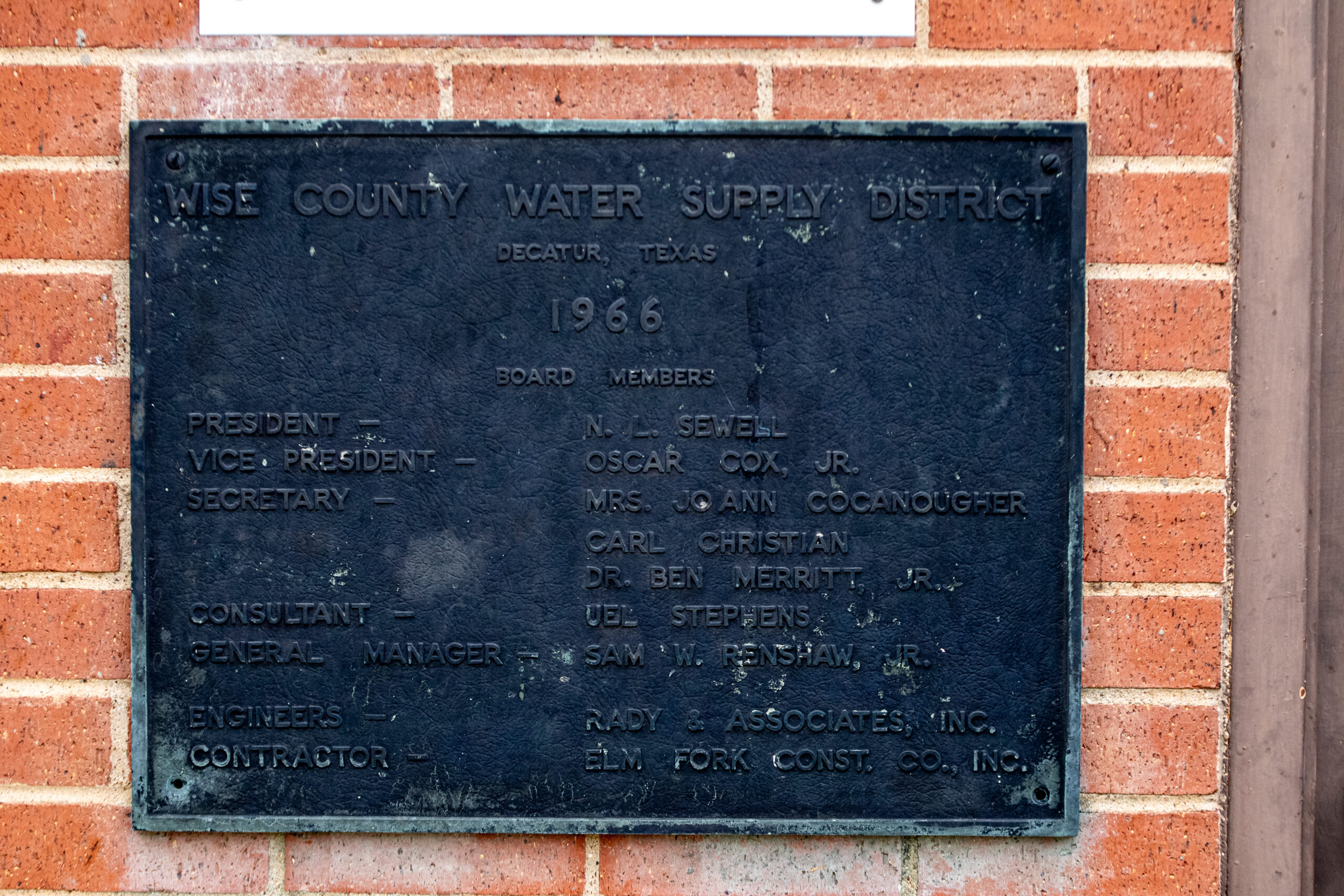

Decatur leaders worked to build this infrastructure around 60 years ago through the Wise County Water Supply District, which only serves Decatur. It’s still in use.

After the pump station and pipeline to Decatur was built, the water board has since invested in additional infrastructure at the site, including a massive back-up generator and other technological and control upgrades situated outside the brick building.

The marker on the building is now green and black from corrosion. The building was built in the 1960’s and has served the city ever since.

The raw water pump station and current pipeline are outfitted to handle up to 3.0 MGD million gallons/day (MGD). Soon, a new raw water pump station and a larger pipeline to increase that capacity is in the works after the passage of the Wise County Water Supply District’s $39.9 million bond earlier this year.

The water board will construct a new, $18.2 million raw water pump station near the lake. Officials are weighing a decision to build the new pump station on new land that would need to be acquired, instead of on TRWD land. Among the considerations for site selection is flooding potential at the current site.

The rest of the bond, $21.2 million, will fund the replacement of five miles of 12-inch pipe between Decatur and Lake Bridgeport with 24-inch pipe.

Mayor pro tem Melinda Reeves, Connor Manley of Kimley Horn, Decatur Public Works Deputy Director Roddy Boston and City Manager Nate Mara stand next to one of the pumps at the raw water lift station by Lake Bridgeport. It is capable of pumping 2.3 MGD.

The pipeline is around 11 miles long in total. Portions of the current line date back to 1965. Due to the amount of water line breaks, much of that 12-inch line was recently increased to 20-inch plastic pipe, which will not be replaced.

The line and pump station project will take around three years to complete. After all upgrades are completed, the waterline is expected to reach the capacity of 6.6 MGD, more than double its current production.

Currently, three pumps transport this water after initial treatment 11 miles uphill towards Decatur’s water treatment plant.

Recent SCADA upgrades are allowing the city to rapidly track quality and potential contaminates in the water being pumped from the lake. Before, the lag time on raw water readings generally took around six hours — which is the amount of time it takes for the water to reach the city from the station.

While the uphill journey to the plant is a logistical challenge, the amount of time and exposure to its pre-treatment chemicals through the pipeline helps eliminate organic matter and contaminates before it reaches the plant.

Water Treatment Plant

One of two clarifiers at Decatur’s water treatment plant.

Driven by a series of pumps, the water journeys up U.S. 380 before it arrives at its next stop, the Royce W. Simpson water treatment plant in Decatur.

The Water Treatment Utility Team, made up of six staff members led by Tony Estes, is responsible for monitoring the treatment process — which includes screening, testing, coagulation, flocculation, filtration and the injection of oxidants like chlorine and other treatments to maintain pH and make the water safe to consume.

The team often adjusts to Lake Bridgeport’s raw water quality on the fly, with organic material and other variables complicating the process. Still, at the plant Tuesday, Boston showed a sample of the raw water quality compared to the finished product.

One looked like tea. The other was clear.

Colton Archa, Decatur WTP operator.

Today, the plant can treat a total of 3.0 MGD of raw water and store 1.6 MGD below ground in storage tanks before moving through the city’s off-site water storage system. The plant maintains the city’s “Superior” water rating. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t face its challenges with adapting to raw water quality changes and demand.

City Manager Nate Mara enters the plant past a large pipe near the entrance of the building named after Royce W. Simpson.

In August, Decatur reached a peak demand of 2.814 MGD. That water usage is expected to surpass 3.0 MGD this year, with it only increasing for the foreseeable future as the city grows.

A team of six employees is responsible for maintaining Decatur’s water quality. Joshwa Payne walks officials through the technical side of the operation at the plant’s office.

In concert with capacity expansions of the water line and pump station, the city is planning to double its water treatment capabilities at the existing plant to 6.0 MGD. The expansion is currently projected to cost $32.7 million. If approved, construction is projected to be completed in 2029.

The tour pauses for photo on one of the water plant’s clarifier tanks.

Potential upgrades to help double the plant’s capacity include: a new 2.0 MGD storage tank, two new clarifiers that would bring the plant’s total to four, a high service pump station, an aeration cascade and a solids handling facility next to the existing sludge lagoon.

While the 3.0 MGD capacity and demand projections seem like it could make for a dire situation soon, Boston explained that water storage and operational changes can manage demand that pushes capacity to the brink — to a point.

Council member Will Carpenter and Joshwa Payne look at the filtration process at the plant.

Based on demand projections, the plant can strategically manage water towers and its 1.6 MGD on-site water storage to get ahead of usage spikes. Another tool available is managing demand through watering restrictions.

Water storage and delivery

Inside the 1 million elevated water storage tower on Thompson Street.

After water is treated its sent upstream to to its water towers.

Decatur’s elevated water storage was recently upgraded, with the construction of the 1 million water tower on Thompson Street and the rehabilitation of the Rose Avenue water tower. The bowls of the water towers are within inches of the same height in an effort to equalize water pressure throughout the system.

It’s one of several water projects that have been tackled recently. Another is the State Street water line project, which you may have noticed while driving through the Decatur Square in 2024.

Thompson Street water tower.

To improve fire suppression capabilities and overall performance in the historically significant area, 12-inch water lines were installed down State Street from Mill Street to Pecan Street along with the installation of 8-inch lines running east off that line down two alleyways on the north and south side of the Downtown Square.

This will support fire suppression systems on the north and south sides of the Downtown Square and allowed for the replacement of a couple of fire hydrants on the square that were out of service.

Another similar upgrade was at Entegris-POCO Graphite and near the new TA Travel Center off U.S. 81/287 to improve stability and water pressure, with infrastructure capable of equipping POCO Graphite with a robust fire suppression system. These upgrades and future improvements were highlighted in the city’s 2016 and 2022 Water and Wastewater Master Plans along with its Capital Improvement Plan (CIP).

An overlooked consideration among water users takes place under the ground, where the water is sent through an underground grid connected to homes and businesses in the city.

The pipe network is a mixed bag in terms of age and quality, with dead ends that can disrupt flow. The city is working to eliminate as many of those kinks as possible to keep flow consistent. Plant staff monitor flow metrics, as well as when it’s disrupted by a break, with the ability to pinpoint issues.

A key consideration is valve sequencing so they ability to shut off each line in case of a break. Andrew Simonsen of Kimley Horn said the repercussions of improper valving can be severe, like when Odessa had a line break between a valve that couldn’t be isolated. The only way to fix the issue was to shut off water to the entire city.

Once water is delivered, it’s used. And when it’s used, it goes into a separate pipeline so that the waste can be returned to nature.

The tour stops at a pump station near the Wise County Jail.

Pumps

The way that wastewater gets to the treatment plant is currently heavily dependent on lift stations and an arsenal of pumps.

The city operates 22 lift stations, like the one pictured below near the Wise County Jail.

A key pumping demand is the wastewater load from the Waggoner branch and Catlett Creek basins to the north of the city, which are sent miles up and downhill to the wastewater treatment plant located near Medical City Decatur. Those basins will represent approximately one third of wastewater flow by 2028.

The pumps for these basins are already taxed by heavy use, evidenced by the storage building that keeps a graveyard of them, as well as parts and potential replacement pumps that may now be functional after repairs that could be brought back into the system in case they’re needed.

A building at the wastewater treatment plant stores several pumps that are broken, require maintenance or ready to be installed in a pinch in the event that another pump breaks. They keep these pumps because there’s a 6 month wait time to order a new pump, and each costs around $60,000.

Engineers with Kimley Horn recommended a simple solution to pump reliance: Using gravity instead.

The topography of Decatur is essentially an inverted bowl, with the courthouse at the top, and everything else on a downslope from there.

While the legacy plant near Bennett Road off Farm Road 51 is downhill from the courthouse, getting influent from the north side of the city required power. Beyond reshaping the topography of the entire city, their solution is to build a new wastewater treatment plant on the north side of the city, where development activity is set to take off.

The Nature Creek Reserve development, projected to include 694 lots in two phases, fast tracked this project. It’s on the former Sewell property on the north end of town. It will be the city’s biggest residential development ever. Coincidentally, it’s also in a property that was recently annexed, unconnected to current city infrastructure.

To facilitate the development on the sprawling, untamed property, the group behind the subdivision agreed to help fund the wastewater infrastructure that will be needed to take on the demand of nearly 700 families moving to town. Paired with the new plant are a series of gravity lines which will replace many of the current pumps.

Public Improvement District assessments and impact fees, which are being paid through the developer and in turn, future residents, are helping fund these upcoming infrastructure projects. For that development alone, contributions include $32 million in PID assessments, plus millions generated from impact fees and other projects outlined in development agreement negotiations.

That plant, identified as the Waggoner wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) is going to cost around $78.9 million to build. Other projects include a Waggoner branch intercepter and gravity lines ($8.7 to $7.6 million), a rehab of the existing plant ($20.2 million) and a future upgrade to double the capacity of the legacy WWTP.

Chase Guinn, Decatur WWTP superintendent, discusses pumping demand in Decatur.

All wastewater projects, including rehab and future capacity upgrades at the current WWTP facility are projected to cost approximately $154 million. Beyond handling future wastewater demands, engineers believe it will bring a systemic upgrade that will eliminate the need for eight pump stations.

The upgrades may also promote quality improvements and more sustainable water usage. If the city were to move forward with membrane filtration upgrades, it would allow the city to consider reuse of wastewater.

Instead of flowing into Lake Bridgeport, the treated wastewater would be injected into the raw water that’s already been pumped from Lake Bridgeport. The idea is to mix in that freshly treated wastewater with raw lake water, which would then go through the water treatment process.

According to Boston, the water product that leaves the wastewater treatment plant is of a higher quality than what is pumped from the lake. It basically has a head start on raw water, and injecting it back to be treated would cut out the middle main. He went so far as to say that the water that leaves the wastewater plant would be relatively safe to use with the addition of a little chlorine.

Wastewater treatment

Natural processes and a strong dose of ultraviolet light are used to treat wastewater.

Decatur’s WWTP was built in 1994. With the capacity to treat 1.2 MGD, it’s average daily demand is expected to surpass the plant’s capabilities by 2027.

But city staff and engineers have a plan. The city is required by Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to begin construction to expand capacity after daily demand reaches 1.08 MGD.

Soon, the city seeks to rehab and expand its existing plant and build a new one, hopefully having its upgrades completed before that demand exceeds the limitations of the infrastructure.

Council member Will Carpenter stands near influent being discharged into Decatur’s WWTP.

While it’s a dirty job, the infrastructure and process to treat wastewater is far from crude.

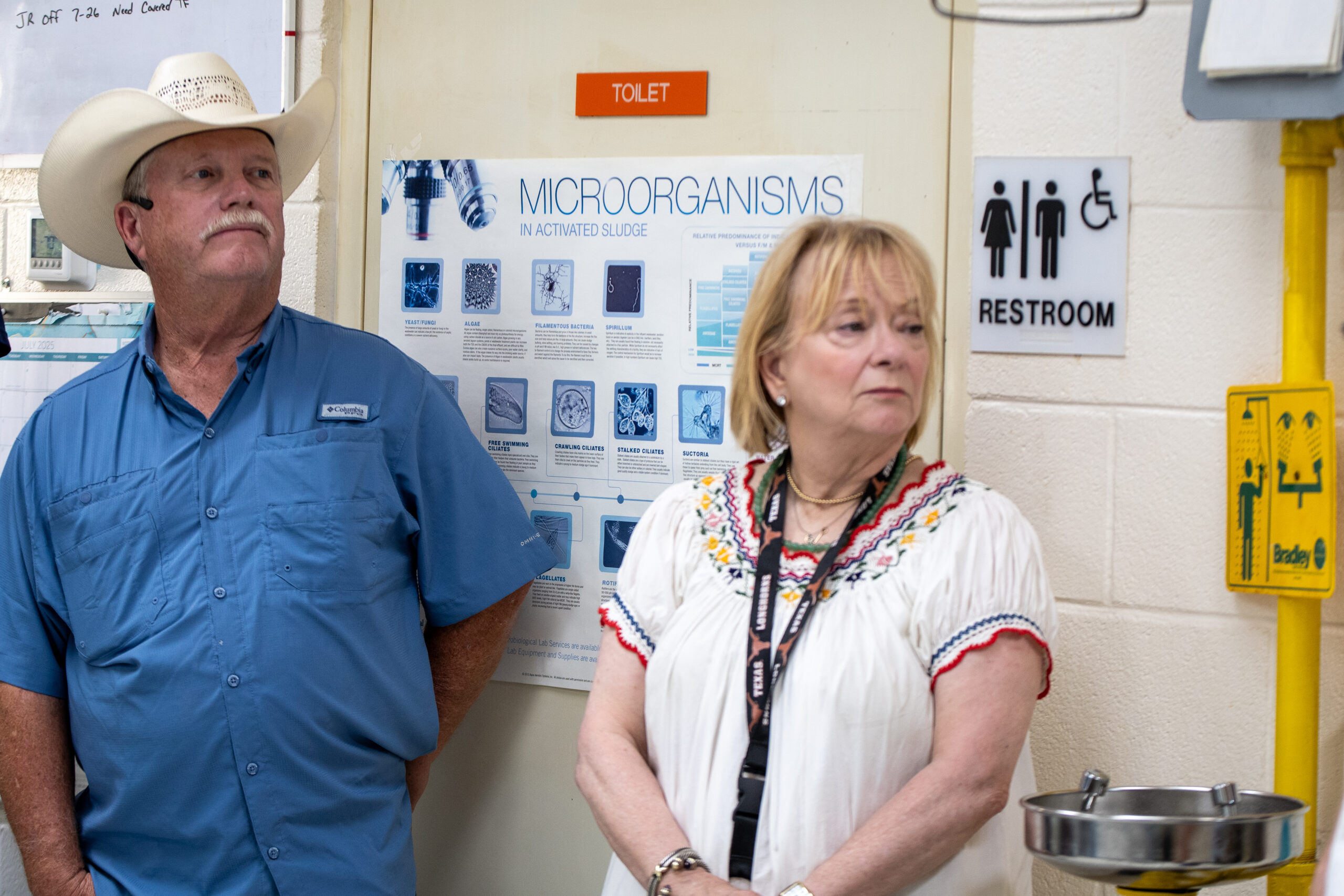

Chase Guinn talks about the wastewater treatment plant on the tour Tuesday.

Decatur Water Board members

There’s six staff at the plant that perform the important job of treating waste so that it can be safely returned to nature. And the people who do it for a living deserve the utmost respect.

How it works

Influent, raw untreated waste, is pumped into the plant for a gauntlet of treatments.

It uses screens designed to trap large objects such as sticks, rags, leaves, plastics, sanitary products, rocks, toys, trash and more. Once separated, these larger solids are plucked out, often by hand, and trashed.

After screening, it enters a second round to remove smaller solids, which are also collected and sent to the landfill. The wastewater then flows to sedimentation tanks or primary clarifiers. These tanks hold it for several hours, allowing lighter materials, like fats, oils, and grease, to float to the top, where they can be skimmed off.

The skimming process can be seen here.

Other heavier particles and suspended solids sink to the bottom as primary sludge which is collected by large mechanical scrapers and pumped out of the bottom of the tank.

Both the skimmed material and primary sludge are sent to solids processing for treatment and disposal. At this point, over 50 percent of the suspended solids have been removed by these physical processes. Next, the clarified water flows into the secondary treatment which uses biological processes to further clean the water.

At this stage, it flows into large aeration tanks where bubbling air provides the microorganisms with an optimal, controlled environment to thrive and consume the organic matter, breaking down the waste materials into carbon dioxide and clean water.

Then a secondary clarification process begins, with the solid particles, including the microorganisms, settle and are sent for solids processing or are recycled. The final step for managing these remaining solids is to send them through a dewatering process, where gravity and physical barriers further remove excess water using a belt filter press, and that is later hauled off site.

Meanwhile the separated liquid keeps moving through the plant. By the time it reaches the final stage, it has been screened, clarified, aerated, clarified again and filtered. It is still important to disinfect the water to treat any remaining bacteria or viruses to protect public health. One of the final lines of defense is ultraviolet (UV) light. Decatur’s WWTP sends the water through a series of chambers that lead to the light mechanism, where the ultraviolet light burns off potential contaminants that may be harmful to nature.

Treated wastewater flows away from the plant, where it will eventually return to the lake.

The water then moves to another tank, and gradually is released back into Lake Bridgeport.

Then the process starts over again.

How is Decatur paying for all of this?

If the city council approves issuing $242 million in certificates of obligation, which are eligible for water and wastewater infrastructure, there will be several funding sources.

The revenue sources to refund the debt will come through development impact fees, PID agreements and the purchase of water and wastewater.

Impact fee eligible projects represent around $205 million of the city’s total capital improvement plan. The city updated its impact fees recently. The new fees are as follows for new single family detached homes: water; $4,780; wastewater, $9,078; roadway, $13,677.

Water and wastewater revenue will also help fund improvements.

Decatur’s new water and wastewater rates will go into effect Oct. 1, 2025. The council approved a plan to increase these rates in increments each year through 2030. The rates, which hadn’t been addressed in years, followed the recommendations from a NewGen Strategies and Solutions study into Decatur’s utility rates. The firm recommended a series of incremental adjustments to catch up with inflation and to help align revenues with future capital improvement projects.

Mayor pro tem Melinda Reeves looks at the names of the Decatur Water Board members and city officials who led water infrastructure projects in the past.

NewGen measured the average monthly combined water and wastewater bill of Decatur residents under current and future rates, using winter averages, 6,000 gallon (water) and 4,400 gallon (wastewater) on 3/4 inch lines as the comparison point.

The current average monthly total water and wastewater bill for Decatur residents is $88.81 ($50.45 water, $38.36 wastewater), under that usage scenario.

The new rates would increase Decatur’s average $100.07 a month ($55.33 water, $44.74 wastewater) in 2026, $106.74 ($58.01 water, $48.73 wastewater) in 2027, $113.40 ($60.69 water, $52.71 wastewater) in 2028, $120.06 ($63.52 water, $56.54 wastewater) in 2029 and $126.72 ($66.34 water, $60.38 wastewater) in 2030.

The increases include a higher fixed charge each year, reaching a minimum $35 minimum charge on water by 2030 for customers on a 3/4 inch line. The fixed charge for wastewater will reach $40 by 2030.

The bill in 2030 would be competitive with comparable nearby cities in 2025. He pointed out that Aledo, Northlake, Rhome, Boyd, Justin and Sanger’s average home water and wastewater bill each totaled more than $127 this year, under the same parameters. Decatur expects to add 500 new water and wastewater connections to the city each year.

The city council is expected to consider these upgrades soon, with a second tour slated next Saturday.

Tuesday’s tour crew included several city staff members, water board members and elected officials.

Loading Comments